대한민국 방문 조사 결과 보고서 (2021)

Mission to the Republic of Korea (2021)

/ 배포일 2022. 7. 8.

I. Introduction

A. Starting off

1. This report was finalised in winter 2021 after evaluating the preliminary results of the country visit via meetings held on-site in the Republic of Korea during the period 15-26 July 2019, and cross-checking these with follow-up research and developments to date. The benchmarks used for this report include the privacy metrics document released by the UN Special Rapporteur for Privacy, Professor Joseph A. Cannataci (“the Special Rapporteur”). 1 )

2. Some of the content of this report reflects and builds upon findings already published in the end-of-mission statement published in Jul9 2019 2 ) as further validated to 06 April 2021. It also contains important up-dates gathered during close monitoring of the situation in Korea since August 2019.

3. The mandate has also continued a healthy dialogue with the Government of the Republic of Korea over various matters, most latterly that of COVID-19 and privacy (November 2020).

B. Acknowledgement and thanks

4. The Special Rapporteur thanks the Korean Government for the open way in which it greeted him and facilitated his visits. Discussions with Government officials were held in a cordial, candid and productive atmosphere.

5. The Special Rapporteur likewise thanks Civil Society, members of the Law Enforcement and intelligence communities, governmental officials and other stakeholders who presented him with detailed documentation and provided detailed briefings.

6. The Special Rapporteur thanks those members of the Korean Parliament, the local Government in JeJu Province and their staff who met with him and answered questions, providing insights into issues of primary concern regarding privacy.

II. Constitutional and other legal protections of privacy

7. Korea’s jurisprudence reflects a Constitution which explicitly protects privacy and related rights in at least three sections:

Article 16

All citizens shall be free from intrusion into their place of residence. In case of search or seizure in a residence, a warrant issued by a judge upon request of a prosecutor shall be presented.

Article 17

The privacy of no citizen shall be infringed.

Article 18

The privacy of correspondence of no citizen shall be infringed

8. The right to free development of personality as protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Articles 22 and 29 and as explicitly linked to privacy by the UN Human Rights Council 3 ) is not explicitly articulated in Korean law.

A. Surveillance

9. The Special Rapporteur has examined the activities of police agencies and intelligence services in order to determine whether any privacy-intrusive actions, and especially surveillance measures, are provided for by law and are necessary and proportionate in a democratic society. There is copious evidence, either received from civil society in the country, or available in the public domain or otherwise procured independently, of abusive behaviour by both the Police and the National Intelligence Service.

10. The senior officials of the National Police Agency whom the Rapporteur met did not comment on specific cases currently sub judice, but neither did they deny past abuses. Moreover, they undertook to make all efforts to make up for and prevent any past mistakes from being committed again in future. Efforts include new regulations to prohibit police surveillance against civil organizations and setting up a new compliance team which monitors the legitimacy of activities of intelligence officers.

11. The National Intelligence Service also met the Special Rapporteur and he was pleased to carry out very open and frank discussions with senior officials. The mandate therefore, was able to give the NIS the opportunity to present their side of the story and to hear how it proposes to prevent past mistakes from being committed in future. The Special Rapporteur concludes that media reports about significant recent internal reforms by incoming Director Dr. Suh Hoon are correct and that significant progress has been achieved since with regard to human rights protection. The NIS “humbly accepted” the evidence, which proves the multiple allegations brought against it for the period up to 2016 and was very open to discuss options which would help ensure that no similar infringements of privacy would re-occur.

12. The Special Rapporteur has taken note of the very detailed evidence presented by civil society as well as the published results of the findings, decisions and recommendations of the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court, the National Human Rights Commission and various official inquiries undertaken by the Government or on its behalf over the past two decades. When taken together with the evidence collected in person during this visit, these elements point to systemic and multiple serious infringements of the right to privacy by both the National Police Agency and the National Intelligence Service up to the period of late 2016 and possibly the first half of 2017.

13. The National Intelligence Service has commenced its reform in a significant manner since June 2017 with a number of measures initiated by its new Director:

(a) the abolition of its domestic intelligence collection function;

(b) the removal of intelligence officers embedded in various areas of government;

(c) the reinforcement of its legal unit through recruitment of considerable numbers of new staff;

(d) appointing legal compliance officers in each division;

(e) creating a Reform Committee with external participation of leading lawyers, academics and members of civil society;

(f) Creating internal inquiries about past misdeeds;

(g) Suspending use of a number of privacy-intrusive technologies including RCS;

(h) Reinforced human rights and legal compliance training in both induction and regular in-service courses.

14. It is also clear that the National Assembly of Korea is well aware of the problems of abuse and accountability, especially in the National Intelligence Service and at May 2020 reported the existence of up to sixteen (16) pieces of draft legislation intended to thoroughly reform the NIS. These draft laws were abolished by the expiration of the National Assembly in May 2020. The National Assembly passed the revised National Intelligence Service Act on 13 December 2020, to reform the Service and the amendment came into effect since 1 January 2021

15. The Special Rapporteur noted with concern that, on several occasions, activists, protesters or members of social movements have been subjected to surveillance by the police that was either unnecessary and/or disproportionate. The arbitrary surveillance of activists and human rights defenders is not new: in 2013, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya, asked the Government to conduct prompt and impartial investigations of all allegations of surveillance against human rights defenders and hold perpetrators accountable (A/HRC/25/55/Add.1).

16. Perhaps the most compelling case witnessed by the Special Rapporteur 4 ) was that of the families of victims of the SEWOL ferry disaster on 16 April 2014, where 304 persons died and 5 went missing, most of them school children. The accident was found by the courts to be the result of negligence by authorities and the company who owned the ferry. The captain was also sentenced to 36 years in prison for gross negligence. However, when families of the victims initially organized themselves to demand an investigation and fight for compensation, the Government severely obstructed any progress and the Defense Security Commands (a body of the Korean Armed Forces) carried out surveillance on the victims’ families. The Rapporteur positively notes that, due to the excesses of the Defense Security Command in this and other cases, that branch of the Armed Forces has been subjected to deep reform, rebranded and stripped of their competencies on domestic surveillance. The evidence presented so far seems to indicate that the Defense Security Command unfoundedly labelled the families of survivors as sympathizers of the DPRK Government, and illegally collected large amounts of personal data (including online shopping information). They also followed family members and disguised themselves as victims’ families in order to spy on them. The Rapporteur met with one of the family members and was appalled to see that the victims of the worst disasters in the country’s recent history were, again, painfully victimized through illegal surveillance and harassment by the State. Those who should have been consoled, protected and compensated by the State in such a difficult moment, were instead seen as its enemies. The responsibility of the violations inflicted on them must be fully clarified and those found responsible must be held accountable.

17. The Special Rapporteur also met with members of social movements in Daegu and Miryang who have opposed the construction of an anti-missile defence site and of electricity lines. Instead of engaging in dialogue and negotiation, it seems that the State and/or parastatal agencies opted for confrontation and imposition, sometimes through a disproportionate police presence and the intensive surveillance of protesters (including physical surveillance of the private domiciles of elderly protesters at night), even of those who have legitimately exercised their freedom of assembly in a peaceful manner and could hardly pose a security threat. While the Rapporteur can understand the strategic importance of anti-missile defence systems and vital power lines, only those protesters who break the law and pose a serious threat to security should be investigated by the police. Attempts to dissuade protesters through arbitrary surveillance and police harassment violate not only their right to privacy but also their right to freedom of expression and assembly. The Rapporteur welcomes the efforts of the Government to investigate the case through the Truth Commission on Human Rights Violations of the National Police Agency.

B. Surveillance for purposes of law enforcement - CCTV

18. There does not appear to be any permanent deployment of facial recognition technology and none of the Government agencies, including the National Police Agency, reported any intention to introduce such systems into public spaces in the near future.

19. The Special Rapporteur endorses the recommendations made by the Korean National Human Rights Commission to introduce legislation that would provide a proper legal basis for the creation of a national centre integrating CCTV surveillance from all over municipal CCTV systems across Korea.

C. Oversight of agencies carrying out surveillance

20. The Special Rapporteur cannot but echo many of the requests for reform made by many members of the National Assembly as well as those of Korean civil society. He is seriously concerned, in particular, about the lack of effective independent oversight of surveillance and investigatory powers that apparently exists in the country.

21. The Rapporteur acknowledges that one basic essential element of oversight already exists in the important work carried out by the Intelligence Committee of the National Assembly of Korea. That, however, is insufficient insofar that the Committee does not possess either the legal authority or the resources to fully audit, in-depth, the conduct of a specific case, and does not have full unfettered access to the contents of a case file. The Committee does however have the legal authority to review the enactment and amendment of the bills on the organization and duties of NIS as well as its budget and settlement. The Committee also has supervisory authority to request NIS to submit data and information necessary for the review, audit and inspection. In accordance with the amended National Intelligence Service Act in effect since January 1, 2021, the Committee's supervisory power has been further strengthened with more legal causes to request for reports from NIS.

D. Privacy and Children

22. The Special Rapporteur noted that, although it is a fading trend, some elementary school children are still encouraged to keep a personal diary for the improvement of their written expression. Some of them are forced to show it regularly to the class teacher. In this instance, the Rapporteur would advise that the practice of keeping a diary can be preserved as long as the children are accurately informed of the fact that the content of the diary can and will be examined by the teacher and should it contain sensitive information related, for example to child abuse, the teacher has a duty to act upon it.

23. Another concern on which the Rapporteur received testimony, was related to the mandatory installation of CCTVs in child-care centres. He assesses that the current safeguards in place related to how the CCTV footage can be examined, are adequate. The number of requests granted is very small. For example, in Daegu only 2 requests have been granted in 6 months for 2 educational units out of 120.

24. The Special Rapporteur also received complaints that there were cases in which the CCTV footage was leaked to the media during investigations together with the victim’s name, age, address and school name. In the case of a leakage that infringes on the individual’s privacy, the Press Arbitration Commission using the “recommendation system” reviews the content post publication and issues a non-compulsory recommendation that is published on the homepage of the Commission. The Press Arbitration Commission has also issued a set of standards related to the disclosure of personal information in the media. In addition, the Korea Communications Standards Commission can assess possible violations by broadcasters, which can lead to binding measures by the Korea Communications Commission, such as monetary penalties and orders to remove or correct information. The mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the right to Privacy shall, if so agreed by the successor to the current holder of the mandate and especially after a degree of post-COVID normalcy is restored, be considering the extent to which the content of recommendations by the Press Arbitration Commission is of sufficient deterrence value. The mandate should also be considering the extent to which the current framework results in sanctions which are timely and whether any existing recommendations should be made compulsory. The relationship to the imposition of severe fines to media outlets should also be further assessed 5 ) .

25. The Special Rapporteur has assessed complaints from civil society that in a number of schools there exist guidelines, which sanction and impose punishments for dating between school students. The facts of the matter are still being verified since it would appear that some of the data on which some of the complaints relied (2009-2013) may be too dated and the problem may have since been largely resolved. Since 2013 the Ministry of Education has introduced a set of official guidelines on the circumstances in which students can be disciplined and the steps which need to be taken in these cases. It has been reported to the Special Rapporteur that the procedures detailed in the manual have contributed to preventing the taking of arbitrary disciplinary measures which may have been related to the student’s sexual preferences and/or dating activities.

E. Privacy issues and laws not directly concerned with government-led surveillance including Health-related data

Generic Data Protection Law

26. The law on Data Protection (PIPA) is relatively strict and follows standards which, in many cases, come close to those of the EU’s GDPR. However, the issue of the true independence of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC) has been raised as a matter of concern since it does not receive its own assured separate line budget with a statutory authority to recruit its own staff independently of the Government departments, which it oversees.

27. Since the Special Rapporteur’s visit in July 2019 a number of mostly positive reforms of relevant laws have taken place 6 ) .

Good practices in Korea regarding privacy and gender

28. The Rapporteur commends the very positive good practices developed in Korea by both civil society and the Government in the area of on-line gender based violence. Of particular note in the civil society sphere is The Korea Cyber Sexual Violence Response Centre (KSCVR) which mainly focuses on “cyber sexual violence”. Cyber Sexual violence is a form of online gender-based violence, which violates numerous rights, the right to privacy included. Women’s right to privacy is adversely affected in online spaces. In the case of illicit videos circulating online, victims are forced to continuously suffer unless those videos are removed from the Internet. Therefore, deletion support is critical for the recovery of victims.

29. In a move which complements the services provided by KSCVR, the Korean Government recognised that the assistance provided by the existing counselling centres for sexual violence victims is not meeting the needs of digital sex crime victims. Therefore, a separate state-led supportive organization was needed to provide specialized support for victims of digital sex crimes. To this end, the Korean Government opened the Digital Sex Crime Victim Support Centre on April 30, 2018, which provides comprehensive services such customized counselling, deletion and investigation support, and legal and medical assistance.

30. The Korean Government formulated the Comprehensive Measures against Digital Sex Crimes in September 2017. For the comprehensive measures, the Government and the National Assembly revised five acts so as to expand the scope of offenders, introduce stricter punishment, and lay the legal foundation for prompt deletion

LGBTI rights in the Armed Forces

31. The Special Rapporteur received reports that LGBTI persons are subjected to violence, discrimination and to violations of their right to privacy in the Armed Forces of the Republic of Korea. While same-sex relations do not constitute a criminal offence in the country, article 92-6 of the Military Criminal Act, prohibits sex between men. As a result, it has been reported to the Rapporteur that members of the armed forces are questioned, sometimes under threats and intimidation, about their sexual orientation, sex life, and even the identity of their sex partners, which constitutes a violation of their right to privacy. The Armed Forces have also confirmed wrongly using dating apps to identify male military personnel who had had sexual intercourse with other male members of the Armed Forces during investigations in 2017 35 individuals, and attempted to intimidate some of them to hand over their mobile phones in order to identify their sex partners. The Ministry of National Defense stated that, following also the recommendations of the National Human Rights Commission, the investigatory procedures within the Armed Forces have been reviewed in order to make them less intrusive and less intimidating. The Special Rapporteur is concerned that LGBTI individuals cannot serve in the Armed Forces without fear of violence and harassment, and that some of their superiors may occasionally subject them to degrading questionings on their intimate life, which should be of no concern of the State. Considering the fact that the military service is compulsory for all men in the Republic of Korea, the Special Rapporteur was appalled to learn that virtually every non-heterosexual man will have to endure such a regime of fear for a minimum of 21 months of their life. If there is a need to impose restrictions in the private sphere of members of the Armed Forces in certain exceptional circumstances, those should be applied equally to heterosexual and same-sex relations, as all discrimination based on sexual orientation is contrary to the human rights obligations of the Republic of Korea.

Privacy and Smart Cities - New economic activities and Smart City in Jeju province

32. During his visit to Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, the Special Rapporteur met with the Provincial Government’s Future Strategy Bureau. He learnt about the Government’s innovative projects on drones, electric vehicles, blockchain, cryptocurrencies, etc. Some of these projects form part of the central Government’s “regulatory sandbox”, an initiative that allows companies for flexibility in their compliance with legislation in order to foster innovation.

33. While attempts to promote innovation and stimulate Jeju’s (and the Republic of Korea’s) economy are commendable, the Special Rapporteur was concerned to see that none of the Jeju’s plans included Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) prior to their implementation. The Rapporteur understands that in these cases, PIAs were not carried out because, in the judgement of the Provincial Government of Jeju, the plans did not affect the data of more than 50,000 persons, which is the threshold established by law. These considerations notwithstanding, in view of the significant potential impact of some of these projects on the right to privacy, it is urgent that such PIAs are conducted as soon as possible, and in any case before the projects enter an implementation phase, even if currently not mandated by law. Each PIA should ensure that the projects concerned, respect and embed, the principles of “privacy by design” and “privacy by default”.

Health and social security data

34. In 2010 the Ministry of Health and Welfare introduced the ‘Social Security Information System’ (SSIS) for the management of multiple welfare benefit schemes through one electronic system. The Special Rapporteur considers that the system includes adequate safeguards in terms of how the data is being collected from the utility companies and similar government agencies, how the risk analysis is being done and how the information is used when reaching out to potential beneficiaries of the system.

35. In spite of receiving requests by other countries, the Korean authorities are in agreement that, for the time being, medical data should not be considered in the scope of international and regional trade agreements. The Special Rapporteur thoroughly commends this approach, which should serve to prevent the further commodification of sensitive medical data.

36. Access to medical data is given only in very limited cases and only when it leads to a strengthening of the right to health and proper safeguards are in place. The request for access is reviewed by the Deliberation Committee, which includes experts in privacy, human rights, life and ethics and the decision-making process is transparent. The Rapporteur here again draws the attention of the Government of the Republic of Korea to the full version of the guidelines and recommendations on health-data produced by my mandate which should be followed when considering all uses of such sensitive personal data.

Right to privacy of HIV/AIDS-positive persons

37. The Special Rapporteur received reports of violations of the right to privacy of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). For example, under the Prevention of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Act of 1988, persons living with HIV/AIDS are criminalized if, despite being aware of their HIV/AIDS positive status, they engage in act that could potentially spread the virus to another person through blood or body fluid without taking further precautions. PLWHAs in detention have also had their right to privacy violated when their HIV/AIDS positive status was openly disclosed as “special patients”, an expression that inmates and guards knew referred to them being HIV/AIDS positive. The Special Rapporteur notes positively that the Ministry of Justice has acknowledged errors in the management of PLWHAs in prison. It has stopped using the “special patients” banners and is working on raising awareness among its officials in order to improve the respect for their rights, including “a video for correctional officials and inmates to reduce prejudice and negative awareness against HIV infection”. Also, those found to have acquired HIV/AIDS are automatically discharged from the Armed Forces, instead of being offered a position compatible with their condition. Men at the age of conscription found to be HIV/AIDS positive are also barred from serving in the Armed Forces.

Right to privacy in the workplace

38. During his visit, the Special Rapporteur observed a lot of concern regarding the monitoring of workers through electronic devices such as CCTV and mobile phone applications. The use of CCTV footage for disciplinary actions against workers is raising problems in various industries.

39. The Special Rapporteur is pleased to note that PIPA already makes reference to this practice and bans the installation and operation of any visual data processing device in open places except for very specific circumstances. The National Human Rights Commission has also asked for measures to be adopted that would ban the use of CCTV for labour monitoring.

40. These recommendations have been taken on board by the Korean government, which has now introduced a ban on workplace harassment in accordance with the revised Labour Standards Act, which took effect on July 16, 2019. The now amended legislation prohibits harassment at workplaces, which would also include the monitoring of workers through visual devices, and imposes obligations on employers to establish a system to prevent and respond to bullying in the workplace.

Right to privacy in a public health context – COVID-19

41. Korea has been criticised, in some cases understandably so, for its privacy-intrusive approach in handling COVID-19 during 2020. Typically

“In March, the government managed to lessen the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in South Korea by adopting massive testing, data-intensive contact tracing, and promotion of social distancing. The government used cell phone location data, CCTV cameras, and tracking of debit, ATM, and credit cards to identify Covid-19 cases, and created a publicly available map for people to check whether they may have crossed paths with people with the virus. However, some of these measures infringed upon the right to privacy.

Health authorities sent out cell phone notifications to large numbers of people containing detailed information on confirmed Covid-19 cases, including age, gender, and places visited before being quarantined. The extensive personal information made public to assist in tracing also allowed people to identify infected persons, which led to public harassment and “doxing.” 7 )

42. Yet organisations like Human Rights Watch also correctly reported some of the internal criticisms and on-going debate during 2020 “In March, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea criticized authorities for these practices. 8 )

43. The above observations on privacy-related concerns should be placed in an oft-repeated context, typically summarised as follows:

“South Korea’s response to COVID-19 has been impressive. Building on its experience handling Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), South Korea was able to flatten the epidemic curve quickly without closing businesses, issuing stay-at-home orders, or implementing many of the stricter measures adopted by other high-income countries until late 2020. It achieved this success by developing clear guidelines for the public, conducting comprehensive testing and contact tracing, and supporting people in quarantine to make compliance easier. The country successfully managed outbreaks in March and August and gradually gained control of a larger, more dispersed outbreak in December 2020. Overall, South Korea has shown success across three phases of the epidemic preparedness and response framework: detection, containment, and treatment.” 9 )

44. Assuming that the above assessment is accurate, the question is ‘To what extent was the above success thanks to any measures which may be considered to be privacy-intrusive?’.

The key issue is this: were privacy-intrusive measures taken in Korea to tackle COVID:

(a) provided for by law, as well as,

(b) necessary, and

(c) proportionate in a democratic society?

The autumn 2020 report by the Special Rapporteur to the General Assembly about the COVID-19 impact on privacy spells out in greater detail, some of the intrinsic problems in answering this question.

45. It should be stated immediately that in most instances able to be identified, privacy intrusive measures concerning COVID-19 taken within the Republic of Korea generally did have a legal basis. They were provided for by law. The outstanding questions therefore remain were/are these measures necessary and proportionate in a democratic society?

46. In order to properly answer this question, it is important to grapple with some of the detail of what actually happened in Korea. The technologies employed certainly seem to have been successful in drastically reducing the time of identifying where infection is taking place and how it is spreading:

“As COVID-19 began to spread, the South Korean government transformed the “Smart City” data platform it was developing into a public health tracking tool. The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, or KDCA, developed the Epidemiological Investigation Support System, or EISS, a platform that enables public health authorities to rapidly collect and analyze data to track confirmed COVID-19 cases. The system began operating on March 26, 2020, just two months after the country’s first confirmed COVID-19 case. Using the EISS, once the KDCA confirms a COVID-19 case, authorized investigators request each patient’s location data that is entered into the system by respective entities pursuant to Korea’s Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Act. The system then performs real-time tracking analysis, which, complemented by traditional interviews by human contact tracers, enables both quick contact tracing and the identification of pandemic hot spots.

This system has allowed tracking and investigation of confirmed COVID-19 cases in less than 10 minutes, rather than a day or more before the EISS. (emphasis added). Data privacy and security are ensured by making sure that only KDCA investigators with the necessary legal authority can access the EISS, and by logging every system access for security incidents. To minimize the collection of personal information, the maximum data collection period for each case is set at 14 days, the incubation period of the disease. And the system is temporary: At the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, all the personal information will be destroyed.” 10 )

47. The EISS outlined above is the first of several technology-related measures.

“Second, South Korea has been using a smartphone app to monitor compliance by those under isolation or quarantine—those confirmed to have COVID-19, those in close contact with a confirmed case, and international travelers. Throughout the pandemic, South Korea has not closed its borders to any international travelers entering the country. Instead, it has implemented special entry procedures mandating a 14-day self-quarantine and free COVID-19 testing to prevent spread. The Self-Quarantine Safety Protection App is a two-way app that enables the quarantined person to report any symptoms and the designated case officer to monitor the individual’s quarantine compliance via GPS-based location data with consent. While quarantine compliance monitoring via the app is strongly recommended, it is not mandatory. Those without smartphones or those who wish to opt out can be monitored via the traditional method of phone calls by a case officer. Still, the adoption rate of the app was at 91.8 percent as of Sept. 1, and both South Koreans and travelers are reassured by knowing that those at risk of spreading COVID-19 are compliant with self-quarantine measures.” 11 )

48. The following succinct summary explains some of the reasons why the Special Rapporteur finds that a significant amount of personal data collection in the name of combating COVID-19 was 12 ) for certain periods of time, especially in the period January-June 2020, neither necessary or proportionate:

“Disclosed contact trace data (e.g., “where, when, and for how long”) help people to self-identify potential close contacts with people confirmed to be infected. However, location trace disclosure may pose privacy risks because a person's significant places and routine behaviors can be inferred. Privacy risks are largely dependent on a person's mobility patterns, which are affected by several regional and policy factors (e.g., residence type, nearby amenities, and social distancing orders). In addition, the results showed that disclosed contact trace data in South Korea often include superfluous information, such as detailed demographic information (e.g., age, gender, nationality), social relationships (e.g., parents' house), and workplace information (e.g., company name). Disclosing such personal data of already identified persons may not be useful for contact tracing whose goal is to locate unidentified persons who may be in close contact with confirmed people. In other words, for contact tracing purposes, it would be less useful to disclose the personal profile of the confirmed person and their social relationships, such as family or acquaintances. The detailed location of the workplace could be omitted because, in most cases, it is easy to reach employees through internal communication networks; an exceptional case would be when there is a concern of potential group infection with secondary contagions. Likewise, it is not necessary to reveal detailed travel information of overseas entrants (which were not reported in the main results), such as the arrival flight number and purpose/duration of foreign travels.” 13 )

49. Having noted the foregoing prima facie unnecessary and disproportionate collection of personal data, the Special Rapporteur also draws attention to ongoing and consistent attempts by the Korean Government and institutions at increasing privacy protection despite COVID-19 measures e.g.

(a) “In June and October 2020, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidance not to publish patient age, sex, nationality, workplace, travel history, or home residency location, although some local governments still disclose some individual travel histories despite being directed against it. Concerns related to the collection and processing of sensitive personal information, which can reveal intimate information like a person’s sexual orientation and private relations, remained.” 14 )

(b) In March 2021, the South Korean Government asked the public to use their encrypted personal numbers, instead of phone numbers, to protect privacy when they have to write down entry logs at places like restaurants and cafes as part of measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. During February 2021, the Korean government rolled out a new privacy protection measure allowing people to use encrypted private numbers for visits to such places: an encrypted number consists of a combination of four numbers and two letters, and it cannot be used for phone calls or text messaging. It can be converted by authorities only when there is an urgent need to contact the holder of the number for virus-related reasons.” 15 )

50. The Special Rapporteur concludes that, in its attempts at combating COVID-19, the Government of Korea took a number of privacy-intrusive measures which, in some cases, were neither necessary or proportionate but that in most, if not all of these instances, it realised that it had made a mistake and sought to rectify that error through corrective measures (see the example above).

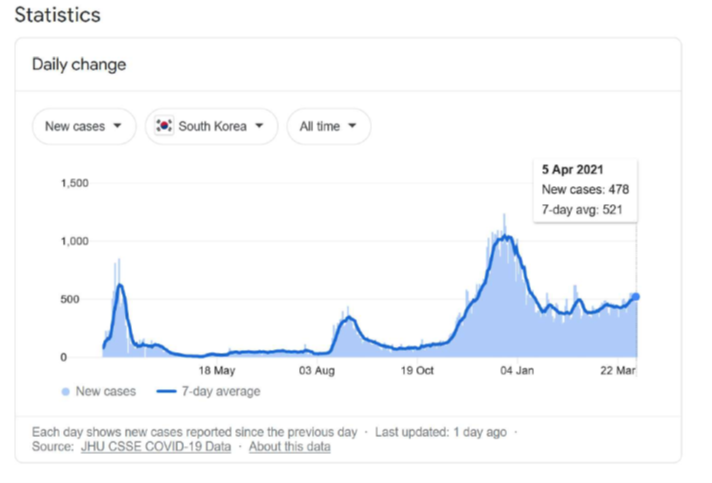

51. The chart reproduced in Fig.1 below illustrates the progress of COVID-19 in Korea to 5 April 2021

52. Three waves of the COVID-19 pandemic are apparent since March 2020 in the above Figure 1. Of special interest is that though the wave dipped significantly after the third wave in January 2021, it has now (March-April 2021) only receded to a level close to what was previously that of the highest peak in the first wave in March 2020 i.e. approx. 530 new cases a day. The reasons for this level of infection despite all the privacy-intrusive safeguards in place, are not clear at the time of submission of this report on 6 April 2021. Thus, conclusions at this stage can only be preliminary since more data is required across a longer time-span for definitive findings to be established. The jury is therefore still out as to whether any or all privacy-intrusive measures regarding COVID-19 as taken by Korea were necessary and proportionate. This makes it difficult to identify which good practices, if any, one may find in the Korean approach to privacy in the context of COVID-19. Considering the possibility that, when re-visiting the situation in 12-36 months from now, some or all of the following answers may be relevant, the Special Rapporteur reproduces below, the answers provided to his questions by the Government of the Republic of Korea in November 2020. In most cases the questions and responses are self-explanatory and further complement and often corroborate the analysis provided above in this section dedicate to COVID-19 and privacy in Korea.

53. Following his visit, the Special Rapporteur addressed a questionnaire on the right to privacy to the Government of the Republic of Korea (see appendix). The questions contained related to law and policy (such as the current legal framework for data-collection for health purposes, including data on COVID-19 and its handling); the development of dedicated applications, contact-tracing and emergency alerts, and related security considerations; standards adopted by institutions to protect the confidentiality of data; and awareness-raising measures with regard to legal limitations to data collection, and the recourse citizens have in the event of violation of limitations. The Government replied to the questionnaire on 3 November 2020.

III. Conclusions and recommendations

A. On intelligence oversight, security and surveillance

54. In the light of the above, the Special Rapporteur therefore draws the attention of both the Government of the Republic of Korea and the National Assembly to the following issues and invite them to take urgent action and maximise the opportunity afforded by upcoming debates in the National Assembly about legislation currently in draft form.

55. The recent changes to the National Intelligence Service Korea Actvoted into law on 13th December 2020 have been heavily criticized 16 ) on a number of grounds and in no way do they implement the recommendations made to the Government of the Republic of Korea by the Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy in June 2019.

56. The legal basis and the regulatory framework for surveillance by both the National Police Agency and the National Intelligence Service is inadequate and is in need of urgent and comprehensive reform.

57. The internal audit functions of both the National Police Agency and the National Intelligence Service of the Republic of Korea should be significantly reinforced by the creation of standing teams including representation of the Director of Human Rights Protection of the respective agencies. These teams would be empowered and tasked with the end-to-end audit of specific cases, selected both on an “own initiative basis” and a “random sampling” basis, in addition to investigation of complaints brought against individuals or units.

58. The current powers granted by law to the Intelligence Committee of the National Assembly are too limited and, in practice, prevent it from carrying out effective oversight of the National Intelligence Service. They should be widened considerably.

59. The National Intelligence Service should conduct an in-depth revision of its culture and practices of opacity, whether self-developed or imposed by law. Making sure that only information that needs to be kept secret is in fact secret, would allow Korean society to better understand the role and working methods of the National Intelligence Service. Ultimately, and together with strict oversight and adherence to the law, it would help the National Intelligence Service to gain trust from Korean citizens.

60. There should be created a new independent full-time body which could be called the Surveillance and Investigatory Powers Commission (SIPC) whose work should complement that of the Intelligence Committee of the National Assembly of Korea.

61. This new independent entity (SIPC) should:

(a) contain a blend of senior judges (serving and/or recently retired), ICT technical staff and experienced domain experts with a successful track record of working in the police and/or the intelligence services, (principle of multi-disciplinarity) tasked with oversight both ex ante and ex post;

(b) employ people in adequate numbers (principle of adequate resourcing)

(c) who would have full authority provided for by law (principle of full legal basis)

(d) to carry out frequent and regular (at minimum once a month) snap-checks of both intelligence agencies and police services (principle of full authority and complete unfettered access) in order to

(e) assess whether any surveillance being carried out is legal, necessary and proportionate (principles of legitimacy, necessity and proportionality).

(f) In line with emerging international best practice, this new oversight body should have full and permanent remote electronic access to all databases held by the intelligence and police forces it oversees (principle of full electronic access).

(g) report independently to the legislature and not to the executive and thus also be subject to the oversight of the Intelligence Committee of the National Assembly of Korea (principle of independence from the Executive branch of Government)

(h) be assigned an independent line budget in the annual financial estimates approved by the National Assembly such that is amply sufficient for it to carry out its duties; (principle of financial independence)

(i) be composed of a part-time Commission appointed by a combination of existing institutions – and not by Government – which would oversee the transparent appointment of a full-time Chief Executive – for our purposes here called the Commissioner – and the remainder of the staff of the new independent entity; (principle of appointment of SIPC Commissioner and staff being carried out completely independent of Government)

(j) The method of appointment of the SIPC is a subject which should also receive close attention and be subject to public consultation, given the apparent lack of trust in Government and politicians evident in Korean society. It is recommended that some of the options that would be explored would include that:

(k) The SIPC would be composed of the following members:

(i) A senior serving judge nominated by the President of the Constitutional Court, who would act as Chair of the SIPC;

(ii) A senior serving judge nominated by the Chief Justice/President of the Supreme Court in consultation with the Administrative Council of Justice/Judges or similar body which may exist in Korea;

(iii) A lawyer experienced in human rights matters nominated by the Korean Bar Association in consultation with the Council of the KBA;

(iv) A retired senior police officer of unimpeachable integrity nominated by the President of Korea;

(v) A retired senior Intelligence Office of unimpeachable integrity nominated by the leader of the Opposition of Korea (the same person as would identified by Article 127 of the Korean Constitution)

(vi) The full-time Chief Executive of the SIPC to be appointed by the SIPC members would preferably (but not necessarily) be a recently retired senior Judge of unimpeachable integrity, preferably with experience of dealing with intelligence, police and surveillance cases;

62. The Special Rapporteur has noted calls by civil society to subject to judicial overview the current unfettered access of police and intelligence services to meta-data about telephone calls and other communication means. Requests for metadata that are considered sensitive do require a court warrant, and amount to around 300,000 requests per year. The figures of metadata requests considered non-sensitive and therefore not requiring a court warrant, however, are staggering, ranging from 6.4 million to 9.3 million per annum and suggest that access to such data is sometimes requested casually and most probably in many cases without being really necessary. It would prima facie appear that the number of requests for access made is possibly much higher than in most other democracies. It may be a good idea to subject these requests to judicial oversight, or very preferably the new SIPC, even if only to improve privacy protection by discouraging casual access and cutting down the sheer number of requests currently being made. If, however, the current numbers persist, it is estimated that 500-800 new judges or persons with legal training and of judicial standing with special ad hoc training on intelligence matters, would need to be recruited in order to cope with the workload (6.4 million requests) which would tend to have to be tackled on a 24/7 basis.

B. Privacy and data protection

63. The Special Rapporteur recommends the PIPC’s autonomy and independence be significantly reinforced through statutory and budgetary provisions, which would allow for completely independent recruitment and staffing. This reform would help the Republic of Korea move significantly closer to the international gold standard established in Convention 108+ in its latest version opened for signature on 10 October 2018. Its strongly recommended that Korea seek accession to this international standard-setting convention, which is today embraced by more than 55 countries from around the world. Reinforcing its Data Protection Authority in the manner here recommended would also doubtless further improve Korea’s chances of speedily obtaining an adequacy assessment by the European Union in relation to the GDPR. Furthermore, it is also recommended that the PIPC be allowed to impose – and collect the revenue from – administrative fines, which should be set to a maximum of 4%-5% of global turnover of the organisation concerned. republic of Korea possesses investigations.

64. The Provincial Government is also planning a Smart City project in Jeju, as an attempt to favour business investment in the island, especially in its prominent tourism sector. The Special Rapporteur has, over a period of several years preceding his visit to Korea, often talked about the risks of Smart Cities. By installing smart sensors to track persons’ activities in the city and aggregating the big amounts of data already being collected from them, Smart Cities could subject its inhabitants to a regime of surveillance even more intense than the one they are already undergoing. Therefore, the Special Rapporteur would recommend that the Government develop safeguards in order to prevent its Smart City project subjecting citizens to the excessive collection of their data by, first, completing a Privacy Impact Assessment. This PIA should be done in cooperation with civil society, especially local communities, and renewed each year because the Smart City is a quickly evolving concept. Other safeguards could be giving individuals the option to be less “surveillable”; developing and adopting disincentives for automated profiling; integrating Privacy by Design and Privacy by Default principles in the project. Finally, in this context too, the Special Rapporteur recommends the Government bear in mind that data produced by citizens, should primarily benefit them. The Government informed the Special Rapporteur that the primary objective of the Smart City was to create an environment attractive to business investment, but that should not prevent citizens being at the centre of its design. Therefore, the improvement and rationalization of city infrastructure and public services should also be primary objectives of data collection.

The Rapporteur recommends that, even before the Constitutional Court decides on the issue, the Government should take the initiative, not only to repeal article 92-6 of the Military Criminal Act (and immediately halting all related investigations), but also training members of the Armed Forces on sexual diversity and privacy, so that LGBTI individuals can serve without fear of violence or discrimination.

C. Privacy and health-related data including COVID-19

65. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity for reflection. Most, if not all, of the issues raised by wearables, computerisation of health records, related use of artificial intelligence, technology applications in contact-tracing and standards to be respected, even in a pandemic, are addressed by the Special Rapporteur’s recommendations on the subject as explained in the accompanying Explanatory Memorandum. The Special Rapporteur therefore respectfully draws the attention of the Korean Government to the Recommendations on the protection of Health Data presented to the General Assembly of the UN in October 2019. The Government of Korea is urged to continue to reflect on the successes – and failures – of using applied technologies, and especially smartphone apps, in attempts to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

66. The Special Rapporteur strongly recommends that the Republic of Korea lend the expertise that it has gained in the use of personal data in fighting COVID-19 by supporting and possibly co-hosting with his mandate a three-day workshop conference about the subject. This would enable experts from all over the world to share their experience in the use of technology and especially smartphone apps in combating a pandemic and identify any possible areas where uses of such technology could be necessary and appropriate in a democratic society.

D. Gender and privacy

67. During the course of his visit the Special Rapporteur could observe instances, when gender could impact the way that privacy is experienced. The Special Rapporteur therefore respectfully draws the attention of the Government of the Republic of Korea to his findings and Recommendations on Gender and Privacy, presented to the UN Human Rights Council in March 2020. 17 ) The principles outlined therein should be closely respected and implemented.

E. Big data analytics, open data, children and privacy

68. The Special Rapporteur respectfully draws the attention of the Government of the Republic of Korea to his findings and Recommendations on Big Data and Open Data presented to the UN General Assembly in October 2018 18 ) and October 2017 19 ) , as well as his findings and recommendations to the Human Rights Council on Privacy and Children 20 ) .

F. Role of the Republic of Korea on the international stage

69. If it were to follow all of his recommendations as outlined above, the Special Rapporteur sees the Republic of Korea as being especially well-positioned to take a leadership role showcasing best practices in matters concerning privacy, encryption and surveillance within Asia, as well as in building bridges with Europe, the USA and other democratic countries around the world.

FootNote

1)

See. ‘Metrics for Privacy -A Starting Point’, Professor Joseph A. Cannataci https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Privacy/SR_Privacy/2019_HRC_Annex4_Metrics_for_Privacy.pdf This document was developed during the period 2017-2019 in order to enable the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy to maximise the number of common standards primarily concerning surveillance, against which a country’s performance could be measured. It was refined at various stages and then changed its status from an internal checklist to a document released for public consultation in March 2019.

2)

Statement to the media by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy, on the conclusion of his official visit to the Republic of Korea, 15-26 July 2019, Seoul 19 July 2019. The two reports should be read together, especially since, for reasons of available space and editing, some observations, available in the 2019 text, may have been omitted from this version of the report.

3)

Resolution 34/7 adopted by the Human Rights Council on 23 March 2017.

4)

Unless otherwise explicitly indicated in the text, the word Rapporteur is, in this report, used interchangeably with the terms Special Rapporteur or Special Rapporteur on the right to Privacy.

5)

The sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic within a few months of the Special Rapporteur visiting Korea has meant that it was not possible to fairly assess whether the recommendation system does in point of fact work or whether it is too weak. Hence the need for ongoing assessment.

6)

See various articles introducing pseudonymisation and other measures in amendments to three privacy laws by the Korean parliament in January 2020 last accessed on 06 April 20121 and at https://www.ibanet.org/Article/NewDetail.aspx?ArticleUid=0D5FD702-179C-42A1-B37D-45D12F4556DA at https://fpf.org/blog/south-korean-personal-information-protection-commission-announces-three-year-data-protection-policy-plan/.

7)

Kenneth Roth, Human Rights Watch country report Last accessed on 06 April 2021 at https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/south-korea.

8)

Ibid.

9)

June-Ho Kim, Julia Ah-Reum An, SeungJu Jackie Oh, Juhwan Oh, Jong-Koo Lee “Emerging COVID-19 success story: South Korea learned the lessons of MERS” last accessed on 06 April 2021 at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-south-korea.

10)

Jiyeon Kim and Neil Richards “South Korea’s COVID Success Stems From an Earlier Infectious Disease Failure”, Jan 29, 2021, Last accessed on 06 April 2021 at https://slate.com/technology/2021/01/south-korea-mers-covid-united-states-democracy.html.

11)

ibid.

12)

Some changes announced in June and October 2020 may have mitigated risks outlined in this section.

13)

Gyuwon Jung, Hyunsoo Lee, Auk Kim, and Uichin Lee “Too Much Information: Assessing Privacy Risks of Contact Trace Data Disclosure on People With COVID-19 in South Korea” Frontiers in POublic Health, 18th June 2020 last accessed on 6th April 2021 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7314957/ and https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00305/full.

14)

Human Rights Watch op.cit.

15)

Abstracted from “Use encrypted personal number for privacy, South Korea tells public” National Herald India, last accessed on 06 April 2021 at https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/international/use-encrypted-personal-number-for-privacy-south-korea-tells-public.

16)

Human Rights Watch, South Korea: Revise Intelligence Act Amendments, 22 December 2020, last accessed on 06 April 2021 at https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/22/south-korea-revise-intelligence-act-amendments.

17)

A/HRC/43/52.

18)

A/73/438.

19)

A/72/540.

20)

A/HRC/46/37.

참고 정보 링크 서비스

| • 일반 논평 / 권고 / 견해 |

|---|

| • 개인 통보 |

|---|

| • 최종 견해 |

|---|